Thursday, September 4, 2008

To Make Stage Blood

Friday, July 18, 2008

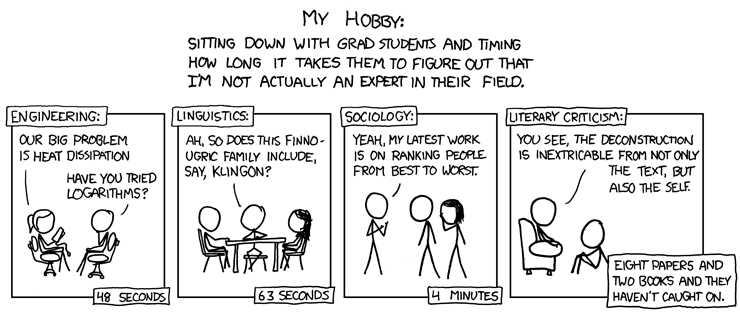

No Love for Derrida

Tuesday, July 8, 2008

Busy Life...or Writer's Block?

I have pages of notes on The Changeling, and I've done a second reading of Jonson's Sejanus (Erin: I like it, especially that fifth act, although I wonder if it would work on the stage), and...I don't know what the problem is. Stuck in the Summer doldrums, I guess.

One thing I am excited about is that I may do a bit of acting, for the first time in like 15 years...just a bit, but still. My old college theatre has given me the chance to present a little Shakespeare at their open house this August, and I've secured the commitment of the remarkable actress who was our Lady Macbeth last year to act opposite me in Act I, Scene 4 of Henry VI, Part 3--that incredible "Molehill" scene with the paper crown and all. I'll be enacting Richard, Duke of York, and she'll be doing Margaret, and it's very exciting--a chance to turn everything up to 11 and really lift the roof off the rafters.

And it's a busy schedule of theatre going, of course--I just saw a superb Merchant of Venice at the Georgia Shakespeare Festival, and I'm flying to Denver on Saturday to see Henry VIII, one of the eight Shakespeare plays I haven't yet seen live on stage. There's a reasonable chance I'll be able to see the last seven by this time next year, God willing and the creek don't rise (All's Well that Ends Well, Timon of Athens, The Two Noble Kinsmen, 2 Henry IV, Antony and Cleopatra, Richard II, and, believe it or not, King Lear).

So, at least I've mustered the energy to check in. Perhaps this will clear the psychic logjam and let me get on with the Great Middleton Experiment.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

A First Look at The Changeling

(Image: Title page of the 1653 quarto edition)

(Image: Title page of the 1653 quarto edition)That long excursion into Macbeth, now concluded, was for me both necessary and rewarding, but threw precious little light on what is supposed to be the central issue of this blog: an investigation of Middleton’s supposed greatness. It’s past time to get to the heart of the matter.

And so we turn to The Changeling, which I’ve just given a first reading.

I picked this play partly for its reputation. As Annabel Patterson says in her introduction for the Oxford Collected Works, “Like Hamlet, the play without which Shakespeare is unimaginable, it has defined Middleton’s canon around itself.” It held the stage for decades after its 1622 premiere (Pepys saw it 40 years later), and has been a popular subject of revival since the late 20th century.

Then, too, there was this intriguing item in Jonathan Bate’s recent essay on Middleton in the Times Literary Supplement:

Two years ago, Declan Donnellan, director of the theatre company Cheek by Jowl, had the inspired idea of staging a double bill of Twelfth Night and The Changeling. A steward in love with the lady of the house: play it as comedy and you have Shakespeare, as tragedy you have Thomas Middleton and William Rowley. “I’ll be revenged on the whole pack of you”, says Malvolio: and he is when he returns as De Flores.

There’s a bit more to it than that, of course, although the steward De Flores casts a long and menacing shadow across the play. His lady, Beatrice-Joanna, certainly goes to darker places than Olivia could have: darker places than could ever be found in the Illyria of Twelfth Night. She is in love with one man, but forcibly betrothed to another. She despises her father’s steward, that creepy De Flores, but knows he’s in her thrall. With a little prompting, he would probably do anything for her. Even a murder?

That calculus leads Beatrice-Joanna down the perilous road that so many Shakespearean characters have followed: commit (or instigate) a single terrible crime, get what you want, and then you’ll be happy and everyone else will just keep playing by the rules as if nothing had happened, right?

Of course not. Crime leads to crime, death to death, with the remorseless logic of an avalanche.

It’s very, very good: dark, haunting, hard to shake out of your mind. I still have a lot of reading and thinking to do, but my first reaction is that it deserves to stand in the first rank of the non-Shakespearean tragedies of the period, to be mentioned in a breath with Tamburlaine or The White Devil.

And how does it measure up to the Shakespearean tragedies? Well, let’s save that discussion for another day. But Shakes would have had no need to be ashamed of this play, had it come from his pen.

There’s a comic subplot, too, thought to be entirely co-author William Rowley’s work—not especially well-connected to the main plot, and tending to draw scorn from modern critics for its handling of mental illness. It’s not without merit, but my first impulse is to look on it as something of a distraction. We’ll see if that changes on a closer reading.

As Samuel Pepys wrote after the 1661 production he attended at the Whitefriars, “It takes exceedingly.” And so it does. I’m looking forward to digging into this one act by act in future entries.

An annotated text of The Changeling is available at Chris Cleary’s Middleton web site. In the Oxford Collected Works, the text is edited by Douglas Bruster, and introduced by Annabel Patterson.

Monday, June 23, 2008

A Revenger's Tragedy Roundup

If you're interested in the press these productions have attracted, The Shakespeare Post has linked and excerpted reviews from various UK papers in two posts:

Theatre Review: Revenger's Tragedies in London and Manchester Both Alike in Blood and Excess

Theatre Review: Revenger's Tragedy Directors Need to Trust the Play's Riches

If you don't know The Shakespeare Post yet, I hope that you will drop in. It will almost certainly become one of your regular blog-stops on the Internet. The author, John D. Lawrence, astonishes with the quality and quantity of his output. And I'm not just praising him because he linked to me once, although it didn't hurt.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Some bloggers are odd feeders!

(Image: Hadrian's Wall east of Greenhead Lough, as photographed by Wikipedia user Velela.)

(Image: Hadrian's Wall east of Greenhead Lough, as photographed by Wikipedia user Velela.)I'd like to mention one of her entries in particular, a discussion of Middleton and Dekker's pamphlet News from Gravesend: Sent to Nobody. Most interesting reading, and I'm sure I'll start here when I want to tackle some of Middleton's non-dramatic writing. The phamplet is mostly about the plague and rich people fleeing London while the poor are left to die, but also features reflections on the new King, James I, and the unification in him of the Scottish and English crowns. Lea's analysis demands quotation:

[T]he de facto union of England and Scotland is figured as a royal wedding in which the maiden isle" surrenders "her maidenhead" to the Scottish king, the newfound permeability of the border a kind of sexual penetration (which, of course, leads us to the inevitable conclusion that Hadrian's Wall is England's hymen I am not sure how to feel about that).

I remember hiking along Hadrian's Wall, and that wasn't the first thing that came to mind. But literature is about opening our minds to new possibilities, no?

Two Engaging Essays

Gary Taylor, general editor of the aforesaid Oxford Middleton, continues to trek around England in his apostolic vein, preaching the good news and waving the good book at his audiences. It was he who coined the epithet "our other Shakespeare," so you can guess that his recent piece in the Guardian, "A Mad World," will be laudatory. He focuses this time on Middleton's play The Revenger's Tragedy, which is today being produced by two (!) theatres in London. Revenger is next on my reading list after the Changeling, so I was happy to have the preview of things to come:

He goes on to say that "Middleton's achievement in The Revenger's Tragedy does not cancel Shakespeare's achievement in Hamlet," which is nice of him. Revenger is, also, one of the very few Middleton plays widely available on video, in a recent adaptation starring Christopher Eccleston and Derek Jacobi. There's more good stuff in that article, including more on this "Shakespeare is Michaelangelo, Middleton is Carvaggio," metaphor that Taylor keeps coming back to. I know rather less about Italian painting than I do about English drama, so I'll leave that one to better minds.

Revenger...audaciously rewrites Hamlet. Against the ambiguous personal madness of Hamlet Middleton set a psychotic world in which "we're all mad people, and they that we think are, are not". Hamlet, a romantic prince, confronts a single evil antagonist, the usurper Claudius. Vindice, an ordinary man, confronts a legitimate royal family, an entire court, an entire political system, violently corrupt. Hamlet disowns his own actions, asserting that he retains a secure, moral, internal identity: his crimes were performed not by Hamlet himself, but by his madness, and "Hamlet is of the party that is wronged" and "This is I, Hamlet the Dane", and "I have that within that passes show". Vindice, instead, dissolves in the vertigo of his own disguises ("Joy's a subtle elf: I think man's happiest when he forgets himself"). At the end of Shakespeare's play, "flights of angels sing" Hamlet "to his rest". Middleton lets no one imagine such an elegiac ending for Vindice, one of those "innocent villains" who discovers and demonstrates that the logic of revenge leads to terrorism and mass murder.

Our second essay is from Jonathan Bate (CBE FRSA FRSL, as his Wikipedia page points out--Oh, to be a Briton! Such titles! Such letters!), most recently a general editor of the RSC Complete Shakespeare. In an essay for the Times Literary Supplement, entitled "The Mad Worlds of Thomas Middleton," he offers an assessment both of Middleton and his new Collected Works that is generally positive, but far less revolutionary: here is a dramatist of great ability, long overdue for a reappraisal, but, ultimately, only one among several of the lesser lights of the period. There's a lot of apples on the tree, kid, but there's only one Big Apple.

I guess I've got to read the rest of those plays before weighing in on that one, but Bate's more measured praise certainly refreshes the palate after Taylors somewhat over-ripe evangelism. Bate is also quite right to stick a pin in some of the more inflated prose in the Collected Works. He rightly calls out this passage for ridicule as embodying "the critical indulgence of the late twentieth century:"

The metaphor of castration foregrounds not the literal status of censorship but its (dis)figurative status; that is, castration figures an originary (and paradoxically productive) lack rather than the loss of an originary plenitude . . . . what looks like defetishism (multiple, small differences constituting a clitoral criticism opposed to the single, big difference of a phallic criticism) from another perspective looks like fetishism masquerading as its opposite.That from Richard Burt's essay on censorship in the Companion volume. Clitoral criticism? As Bate observes, "this kind of thing is so old-fashioned...that it makes the work seem dated even as it comes fresh from the press."

Bate defends the scholarship of the Oxford edition, however, on more important matters, such as the extent of the Middletonian canon. He endorses in particular the inclusion of The Revenger's Tragedy and The Lady's Tragedy (commonly called The Second Maiden's Tragedy), saying their attributions "come as close to settled facts as we are likely to get in this contentious field." He also pronounces Taylor's account of the many tangled texts of A Game at Chess "a scholarly tour de force."

Good essays, both, and well worth a read.